Graz

1600–1809

The time of Counter-Reformation manifested in Graz with new monasteries, churches and Baroque art. In the field of education, the Jesuits were particularly influential. The cultural innovations were accompanied by a loss of political significance of the city: Crowned Emperor Ferdinand II in 1619, the former archduke took the court to Vienna and Graz lost its role as a royal and imperial seat. In 1782, under Joseph II, the city was declared an “open city“ and the fortifications were not further renovated.

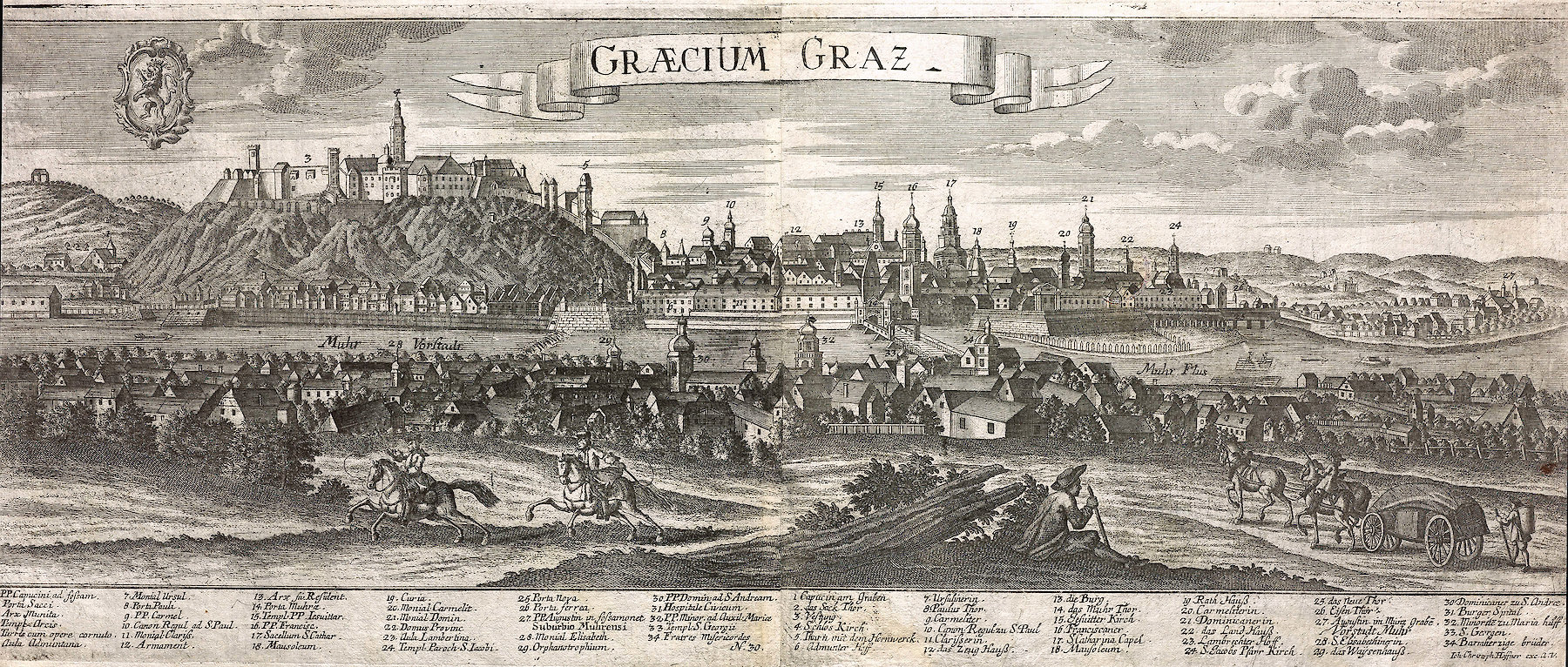

A few decades later, the ideas of the French Revolution came to Graz with the French army and were received with interest by the bourgeoisie. However, the last occupation by the French army in 1809 was warlike in nature and had devastating consequences. The victory of the Napoleonic troops over Austria resulted in the destruction of the mighty Schlossberg fortress, which had shaped the cityscape for more than 300 years.

A Victory Mark Decreed by the Emperor

The Marian column was part of propaganda that celebrated the victory over the Ottomans as a triumph of Christianity over Islam. With the introduction of a Marian holiday Graz wanted to seek protection from Ottoman attacks. Yet Emperor Leopold I recommended to erect a column following the Viennese model. According to the design of master-builder Domenico Sciassia, it was inaugurated on the Karmeliterplatz in Graz in 1670. In 1796, it was relocated to Jakomini Square. When the Marian Column was relocated to its present location at Eisernes Tor in 1928, it was renamed Türkensäule (Turkish Column) and the Ottoman threat was once again recalled.

Emperor Leopold II is watching a parade organised in his honour from a tent. As the successor of his brother Joseph II he is considered as the last enlightened Habsburg monarch.

Overall, three corps units are shown in this image. In the centre, there is the corps of the cavalry next to them on the left side, the corps of the infantry, and to the right, the “Jäger” (riflemen) behind whom the musical corps of the trumpets, oboes, and drums is forming.

Colonel Seebacher (to the left) and Lieutenant Colonel Dobler (to the right) are heading the parade. Master brewer and innkeeper Richard Seebacher heads all corps units as the commander. In 1792, the tradesman Franz Kaspar Dobler follows him in this function. In the latter, he received Napoleon in 1797.

The City’s Loss of Importance:

The painting shows a parade of the Graz Civic Corps, which was performed for Emperor Leopold II in 1790. The Graz Civic Corps had its origin in the medieval vigilantes. Beside taking part in the military campaigns of the territorial rulers, the latter were responsible for fortifying and defending the city, and safeguarding law and order. Maria Theresia centralised these functions by means of standing armies. The vigilantes lost some of their importance, and thus the cities their military self-administration. Only when the French occupied Graz in 1797, 1805 and 1809, did they reappear to ensure public safety, and prevent looting and violent clashes.

The Hauptwache (i.e. the headquarters of the City Corps), where the French occupiers also installed themselves, was located in the City Hall. It was still the plain Renaissance building from the middle of the 16th century, which was demolished in 1803 and replaced with a more representative classicistic building.

Graz was occupied by French troops three times. In 1797, in 1805, and in 1809. In the last year, after the defeat of the Austrian troops near Wagram, the fortress on the Schloßberg was blown up.

During the French occupation, the Graz Civic Corps provided security in the city. Among other things, it had to fulfil guard duties, and prevent lootings and violent conflicts.

Napoleon as Messenger of Revolution

The Emperor of France never visited Graz. But Napoleon did. During his stay in 1797 he was still General of the French Army. The copperplate print shows French occupying forces and the troops of the Graz Civic Corps in front of Graz City Hall. This representation can be interpreted as an image of playful sympathy for the spirit of Enlightenment. The reforms of Joseph II and Leopold II were still resonating and many a citizen of Graz was disappointed by the reactionary rule of Emperor Franz II / I. What the citizens saw in the Frenchmen were messengers of the Revolution heralding liberty, equality and fraternity.

The French Revolution Brings a Modern Legal System to Europe

The French Revolution and the Coalition Wars that followed it changed Europe lastingly. Comprehensive reforms in the judiciary, the administration, and the army transformed France into a modern and centralized nation-state that was regarded as a model by many contemporaries. With Napoleon’s victorious campaigns of conquest, the events came thick and fast. The reactionary powers of Austria, Prussia and Russia had to concede far-reaching structural reforms and legal liberalisation in order to contain the “revolutionary potential” among the population.

During the Coalition Wars, both the urban appearance and the general mood of the population changed in Graz. French troops occupied the city three times: In 1797, in 1805 and in 1809. Although people were initially open to the bourgeois ideals of the French, patriotism mobilised against France in 1809. The result: The Schlossberg fortress was razed.

Borders of France and its Allies (before the Russian campaign in 1812) |

|

French Empire |

|

Territories dependent on France |

|

Holy Roman Empire 1797 |

|

Austrian Empire 1812 |

The Project of the City

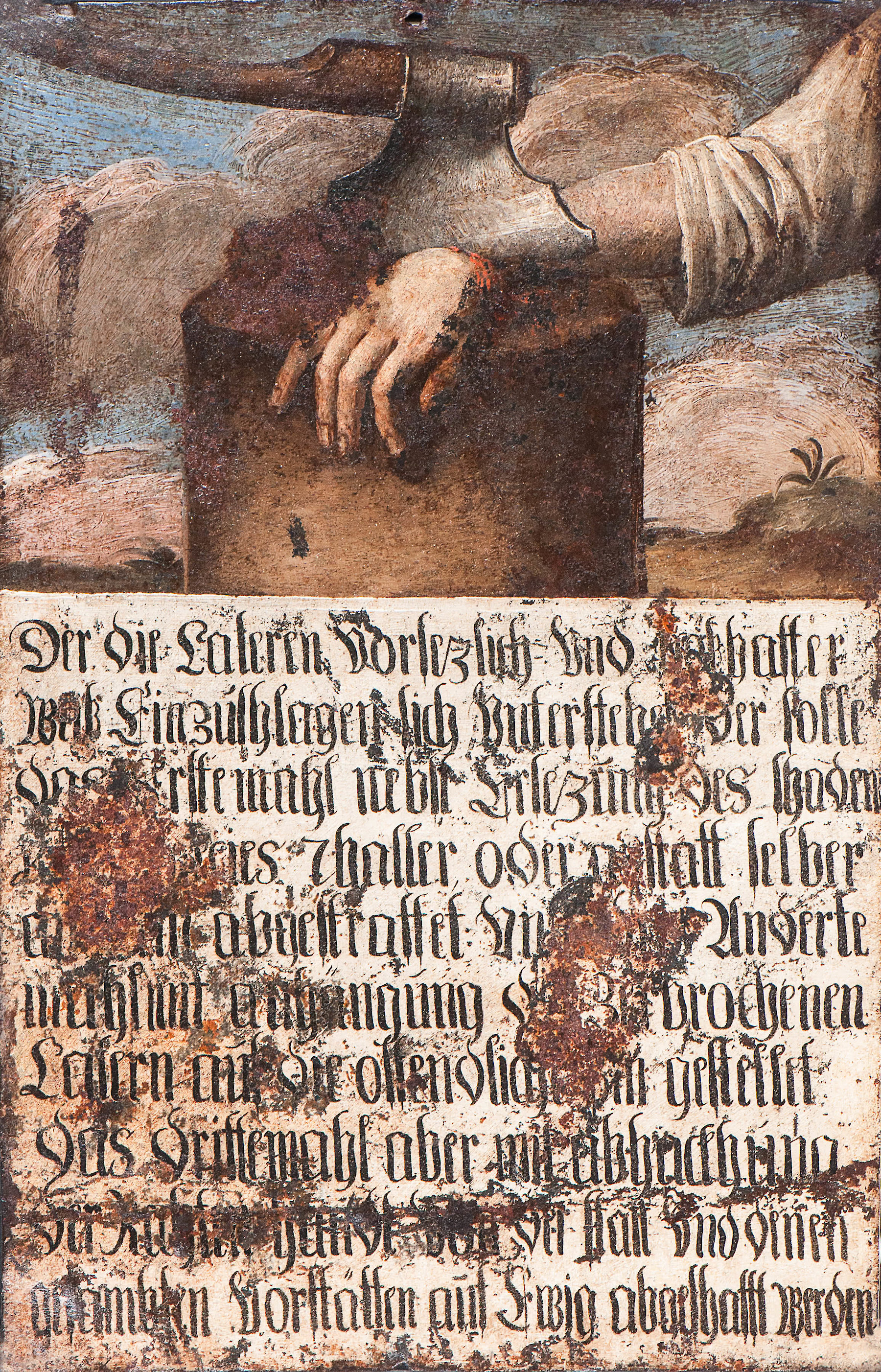

The political culture of the cities was promoted by Renaissance, Humanism and Reformation—also in Graz. In the course of Counter-Reformation, however, the city’s independence was defeated by the absolutist princely state of Charles and Ferdinand. The land-owning (Catholic) nobility gained in importance, the Protestant forces were pushed back violently. The free election of city councillors in town meetings was completely abolished.

The specifically urban political understanding of the guild-master bourgeoisie gradually disappeared in the 18th century. The central state of Maria Theresa and Joseph II turned the self-determined town citizens into citizens of the state. The citizen as state citizen was to become the fundament of a militarily and economically successful state, whereas the influence and the possessions of the previously (tax-)privileged nobility and clergy were diminished.

Gender Roles

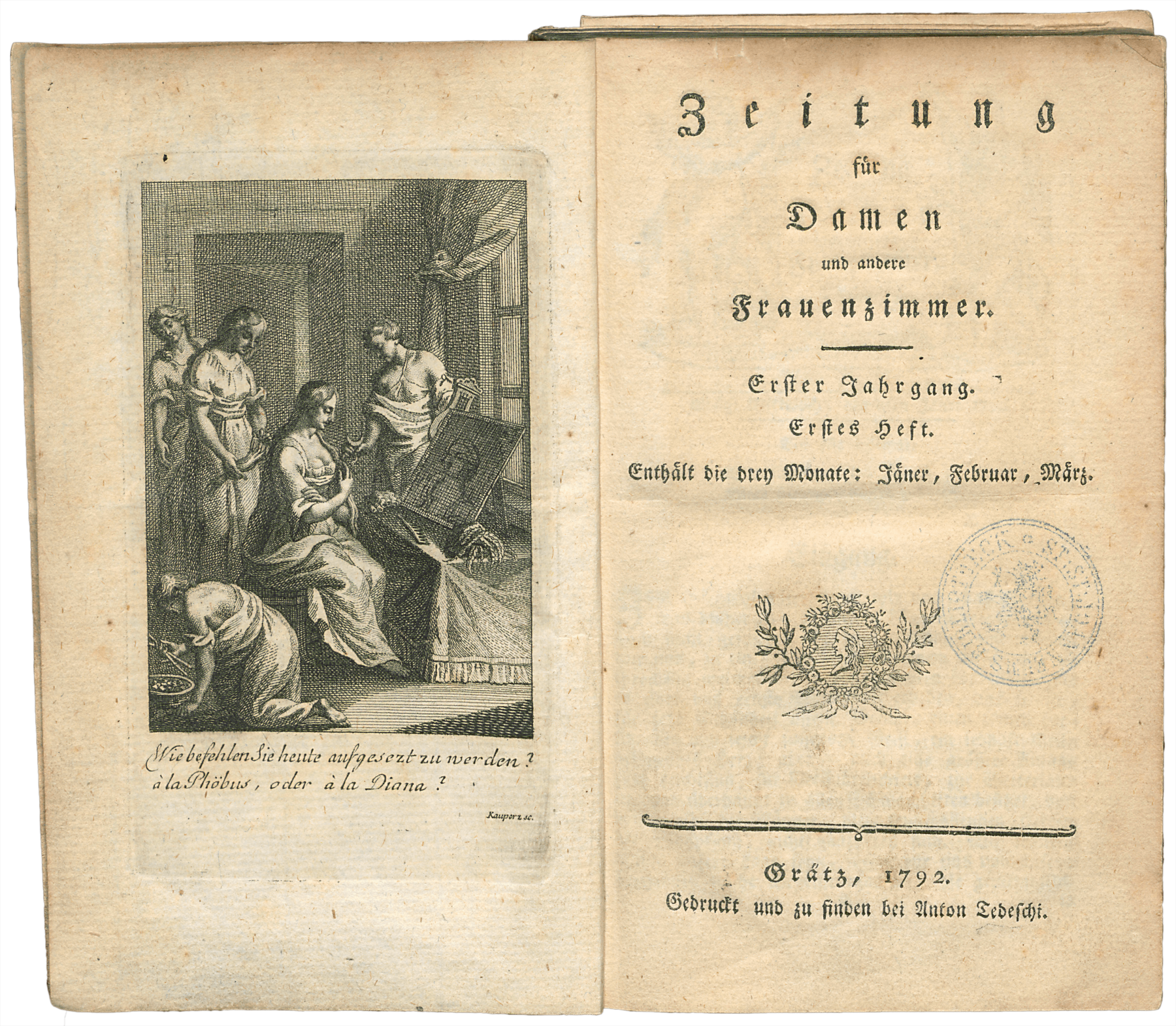

Unsettled by famine, epidemics, and wars, the society of the 16th and 17th century reached its climax of misogyny with the “witch-hunt”. One hundred years later, Enlightenment broke with the “God-given” rule of the nobility and the clergy, and changed the gender relationships with its reforms. Compulsory education, which was introduced by Maria Theresia in 1774, applied to “beyderley Geschlecht“ (both sexes).

The French Revolution strengthened the self-confidence of women. Austria’s first women’s newspaper was published in Graz. Women citizens established political clubs, and claimed women’s suffrage even though civic and human rights were written exclusively for men. Even though all Civil Law Codes formulated the principle of legal equality of the sexes but they also set out the husband as head of the family and guardian of his wife, who had to subordinate herself because of her allegedly weak and unreasonable nature.

Diversity

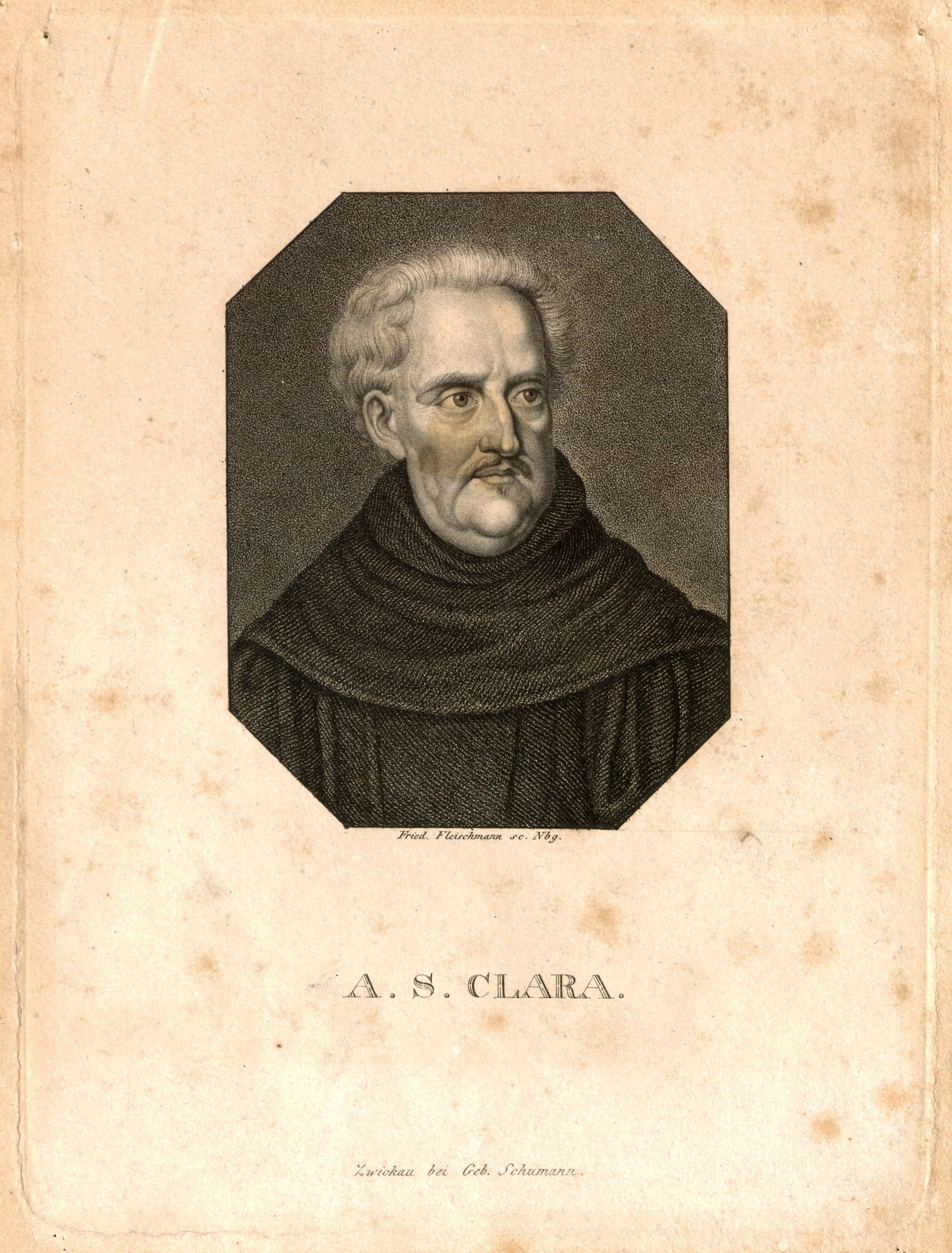

In the early Modern Age urban diversity included only limited religious diversity in Graz. People of different faith were persecuted as “enemies”, “heretics” or “witches. This affected in particular Jews, Turks and Protestants. Emperor Ferdinand II, who was born in Graz, tried to enforce Catholicism with violence when he was King of Bohemia and thus unleashed the disastrous Thirty Years’ War in 1618—it was Joseph II who first granted the Protestants free practice of religion with his Patents of Toleration. The clashes between the Hapsburg Monarchy and the Ottoman Empire were stylized as a religious war of “Cross against Crescent”. And since their expulsion in the late 15th century, Graz remained a city without Jews until 1867.

With the Age of Enlightenment, the pursuit of equality and freedom began, but at the outbreak of the French Revolution and the beginning Napoleonic Wars, Austria adopted a reactionary stance.

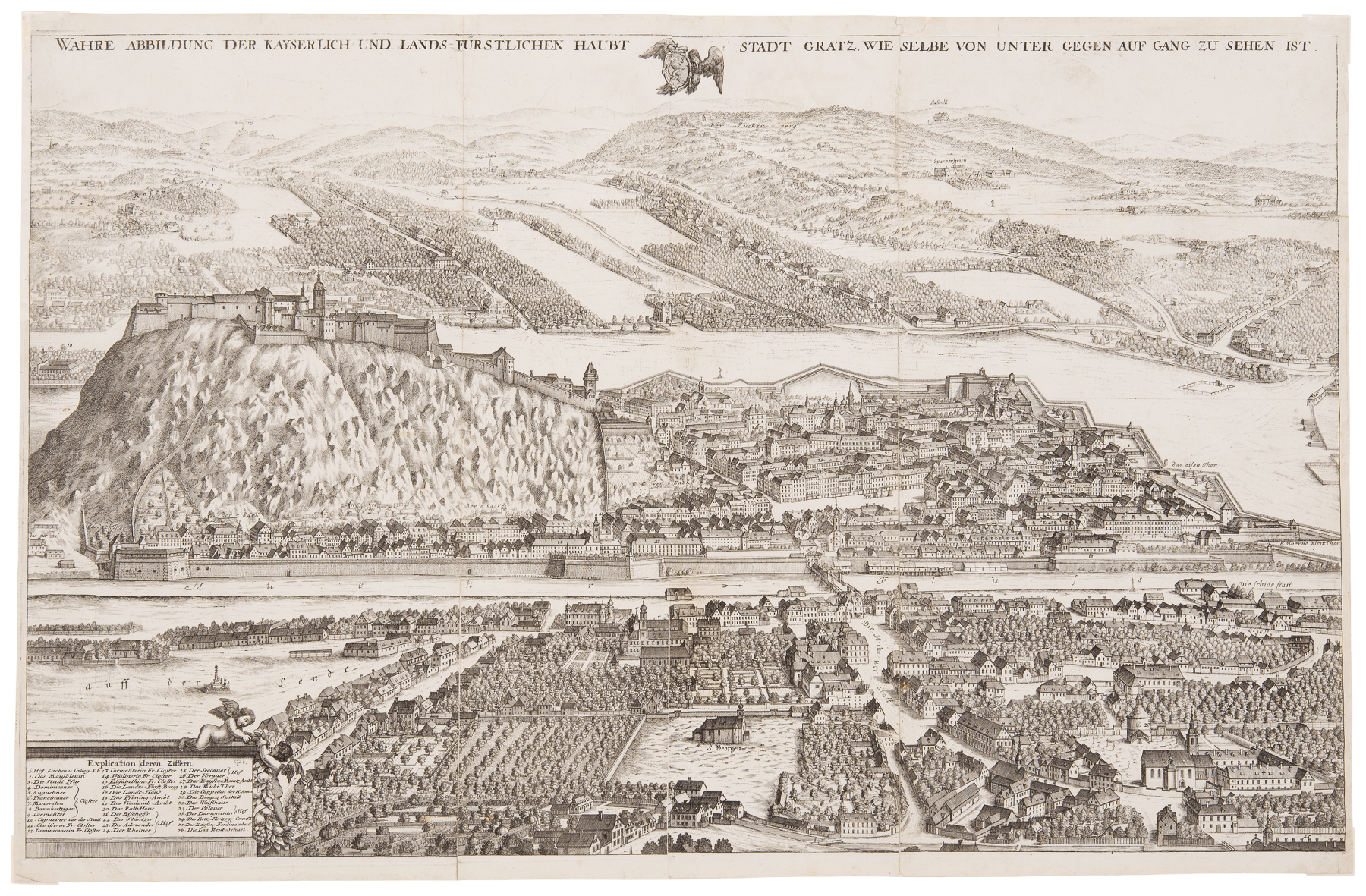

Images of the City

The recatholisation of Styria found expression in church buildings, columns of the Virgin Mary and palaces of the Catholic nobility. Italian architects and artists were popular—the city was given monumental buildings in the Renaissance and Baroque styles. Many houses were demolished outside the city gates to create defence fields against the Ottomans. Its residents then moved to the west, to the historical Murvorstadt.

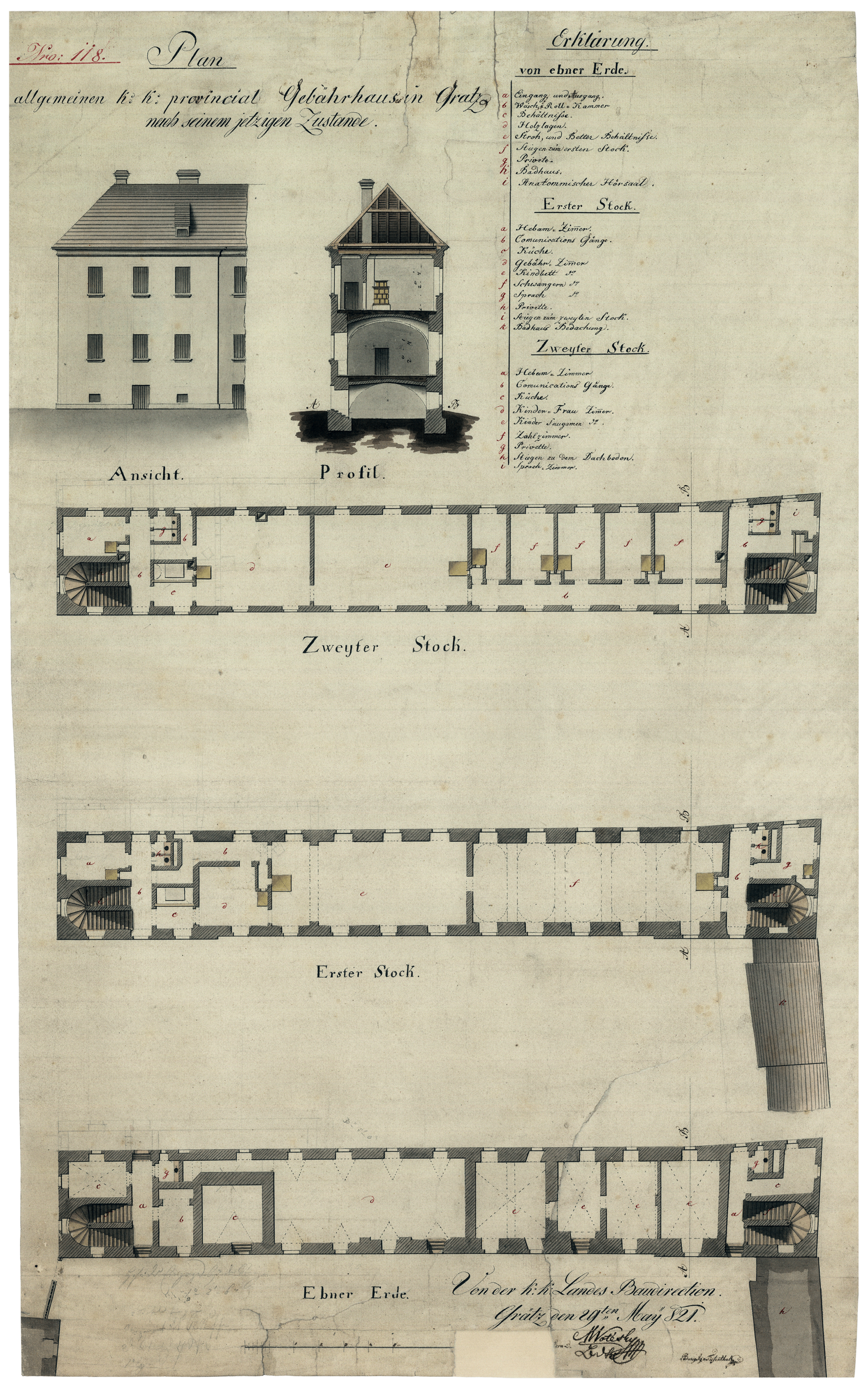

After Joseph II had dissolved monasteries in the 18th century, a “General Hospital” and a “Madhouse” were built on former monastery grounds east of the Schlossberg. Further establishments for education, social disciplining, and welfare followed. The enlightened monarch declared Graz—extremely early in a European comparison—an “open city” in 1784: the city gates remained open; the fortifications were not renewed. In front of the southern gate, a new Vorstadt was created: The Josephstadt, the later district of Jakomini.

Alte Post (Neuhof)

In 1784, the landowner, military offi cer, postmaster, corn factor, and venturer Ritter von Jacomini purchased the Glacis grounds near the Eisernes Tor (Iron Gate) by auction and started to develop a new city area, the so-called “Josephstadt”. And he had a bourgeois townhouse built in a Josephinian style on the Josephplatz, today’s Jakominiplatz, which was created in the process of this. Mail coaches and express mail coaches departed from the Old Posting House into all directions. Today, pizza is served near the Nymphs’ Fountain in the impressive inner courtyard.

Palais Wildenstein

Frederick the Great said about Joseph II that he always tended to take the second step before the fi rst. So many people considered the enlightened despot an experimenter who failed. At any rate, Graz became an “open city” in line with his declaration, and his name is closely related to the dissolution of eight monasteries, the farmer’s market and the establishment of hospitals, lunatic asylums, poorhouses, and penitentiaries. Yet, inside the Graz Federal Police Directorate in Palais Wildenstein, the Josephinian heritage is virtually invisible today. From 1788 to 1922, it was the General Hospital of the population of Graz.

Mausoleum

This tower crowns the burial church of a Habsburg monarch who accomplished at a small scale a prime example of early consistent Counter-Reformation in Graz, and at a large scale, wanted to create a Catholic German empire. Accordingly, he was a main initiator of the Thirty Years’ War after the complete expulsion of all Protestant elements from Graz, in the course of which he had his commander, Wallenstein, murdered. Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II, who was born in Graz in 1578, lies in de Pomis’ Mausoleum.