Graz

1914–1945

The First World War and the inter-war period in Graz were marked by food shortage and social hardship. The newly founded Republic of Austria and democracy did not bring political stabilisation. The geopolitical reorganisation of Europe results for Styria in the loss of Lower Styria, which was deplored across all party lines, and intensified the feeling of crisis.

Graz in the First Republic is determined on the one hand by social reforms, on the other hand it also was the cradle of National Socialism. The activities of the illegal Nazis during the Corporative State dictatorship led to Hitler awarding Graz the title of “City of the Popular Uprising”.

Only seven years passed between the storms of enthusiasm of the population of Graz on the occasion of Hitler’s speech at the Weitzer railcar factory on 3 April 1938 and the bombed city. However, the reappraisal of the crimes of National Socialism and taking responsibility for commemorating the murdered and expellees has continued to this day.

The soldiers carry tornister packs on their backs, and a bayonet, a bullet pouch, and a haversack on their belts. One man had to carry up to 60 kilogrammes of luggage.

The soldiers are in their combat uniforms with coats and caps. Not before 1916, steel helmets were introduced in the Austro-Hungarian army.

As a farewell, the soldiers were decorated with flowers. They stand for the “Spirit of 1914”, the war euphoria, which was both propagandistic and short-lived from the vantage point of the present. Already in late 1914, more than one million Austrian-Hungarian soldiers were either dead, wounded, missing, or prisoners of war.

Into the First World War with Enthusiasm?

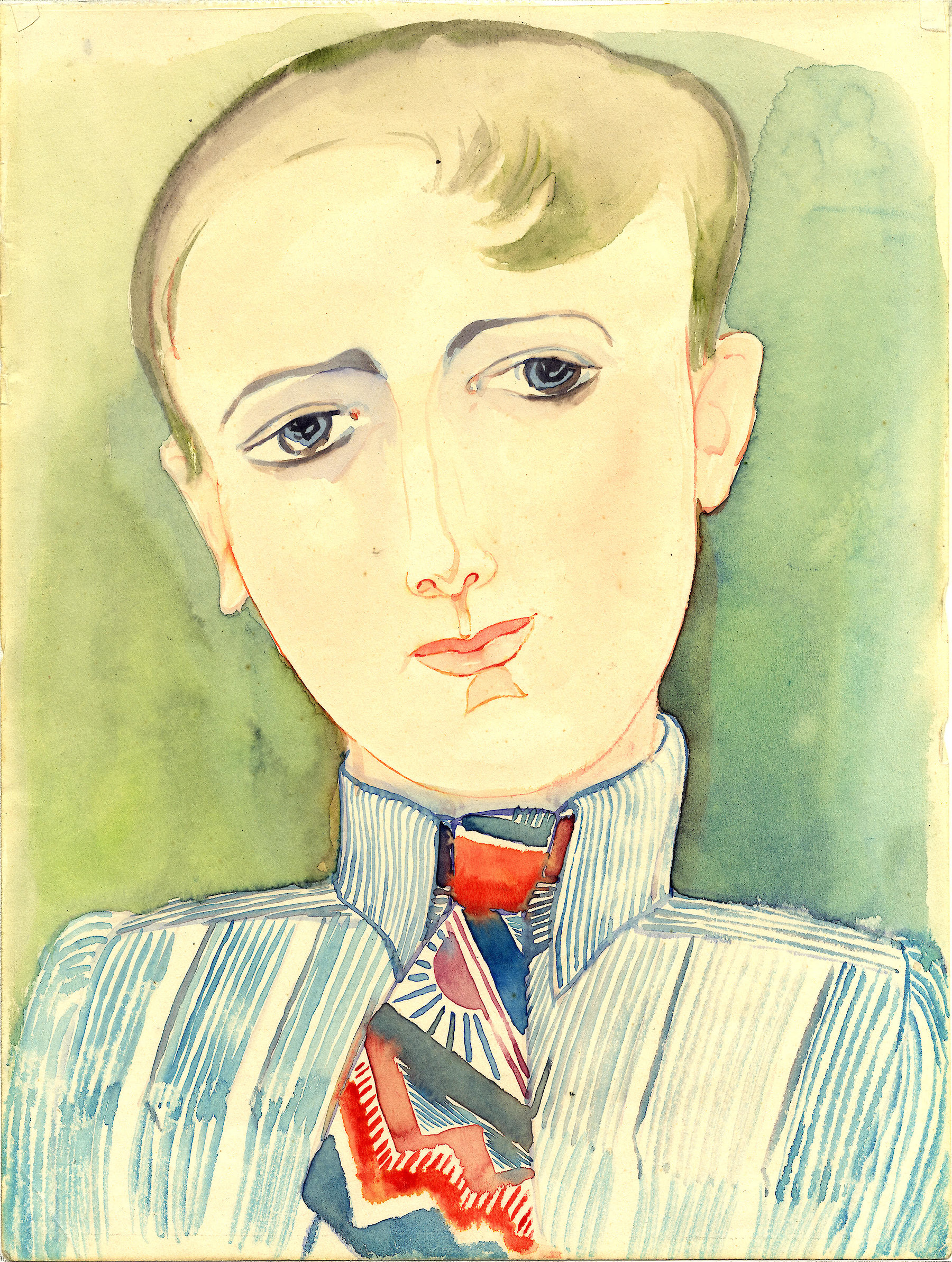

Delirious crowds attending the departure of the soldiers in the summer of 1914 have dominated our idea of the beginning of World War I down to the present day. Franz Köck conveys this cliché only to a limited extent in his painting. He depicts proud joy, but also the pathos of farewell, in a more subtle manner. While the young soldiers enter eye contact with the viewers with inviting confidence, the averted gloomy eyes of the older men evoke compassion.

In the City of the “Popular Uprising”

In 1938, the commercial artist and filmmaker Hanns Wagula documented the “Anschluss” in Graz, the “City of the Popular Uprising”. The film shows the marching in of units of the German Wehrmacht, the Sturmabteilung (SA), the Hitler Youth, and the League of German Girls (BDM) into the inner city of Graz on 13 March 1938. The propagandistic film forges a bridge from free meals given away by young women from the League of German Girls to the programmatic “Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer“ (One people, one nation, one leader). For this, Wagula was honoured with the “Wanderpreis für den besten Berichts- und Propagandafilm staatspolitischer Art 1940” by the Reichspropagandaleitung, the central party propaganda office of the NSDAP.

The Holocaust as the Murderous Culmination of a Culture of Hatred

The anti-Semitic potential that had been built up over decades, especially in Austria and Germany, found its fulfilment in Hitler's delusion of “keeping Germanic blood pure” through the “annihilation of World Judaism”.

By 1940 at the latest, with the systematic murder of people with disabilities, there was a civilization breach that destroyed all normative structures of humanity. From mid-1941 to early 1945, up to 6 million Jews were murdered in the Shoah (the Holocaust)—about 3 million in extermination camps such as Auschwitz, Betzec, Sobibór and Treblinka, about 0.7 million in mobile gas vans, about 1 million in ghettos and concentration camps, and about 1.3 million in mass shootings, primarily on the eastern front.

In 1934, the Jewish Community in Graz had 1,720 members. After the “Anschluss” in 1938, Jewish citizens were systematically persecuted. In the spring of 1940, National Socialist mayor Julius Kaspar declared the city of Graz “free of Jews”.

Jews murdered between 1 September 1939 and 8 May 1945 |

|

Border German Empire 1942 |

|

Borders 1937 |

|

German Empire |

|

Territories occupied by the German Empire |

|

Occupied by Germany as from 11 November 1942 |

|

Allies of the German Empire |

|

Territories occupied by the Allies |

The Project of the City

The First World War manifested itself in Graz through starving masses, military quartering and wounded soldiers. The dissolution of the municipal council in 1914 interrupted civic political co-creation which could only be resumed after the (first free) elections in the First Republic.

In the decades that followed, the municipality had to cope with the consequences of the defeat—refugees, war veterans, economic misery and a precarious housing and supply situation. Social Democratic mayor Vinzenz Muchitsch sought social balance and still inexperienced democracy, which set “red Graz” in contrast to conservative Styria.

The “civic” idea reached its limits at a time of increasing radicalisation and the elimination of basic democratic rights. With the National Socialist assumption of power, civilized society came to a standstill and so did the civic project.

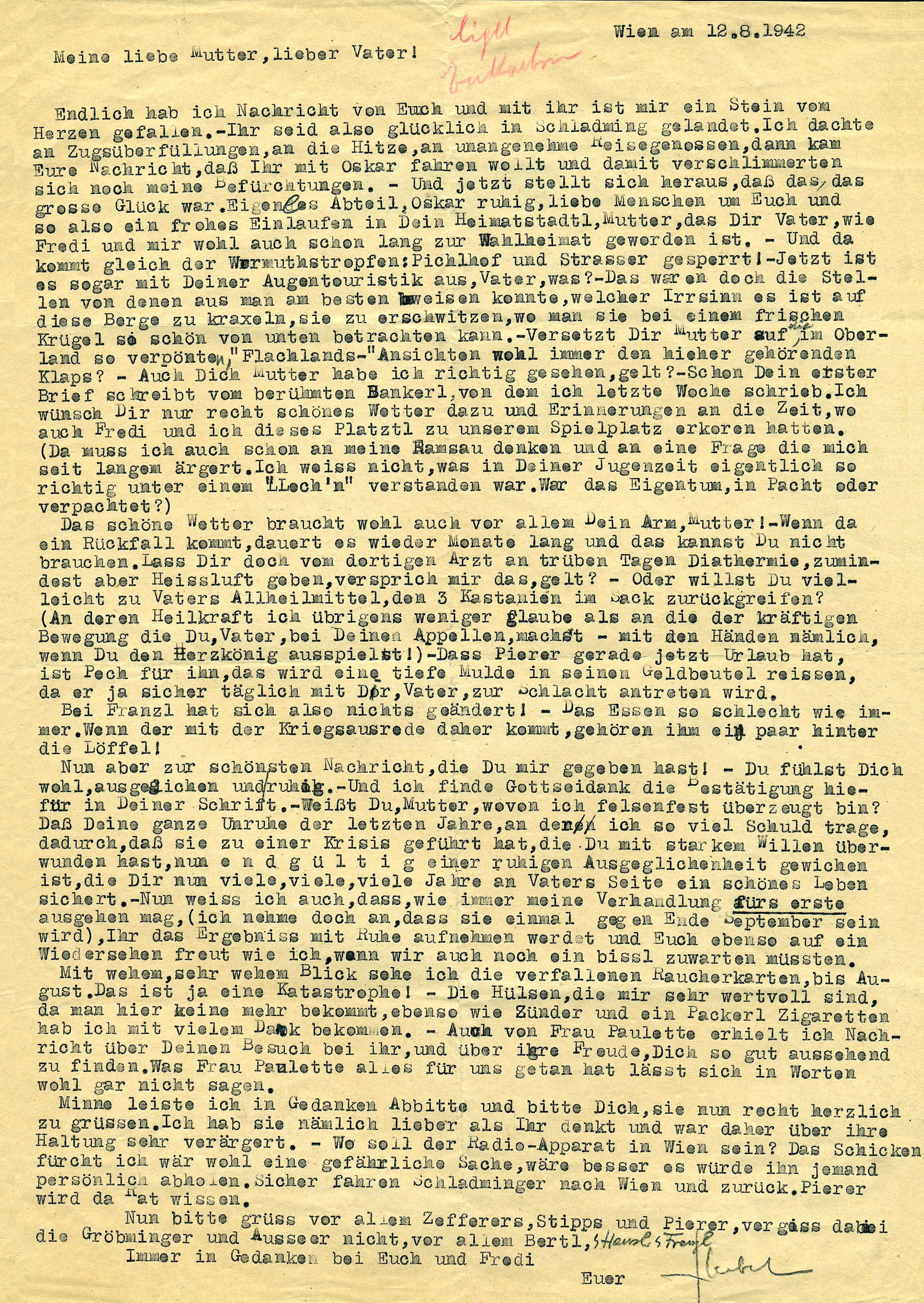

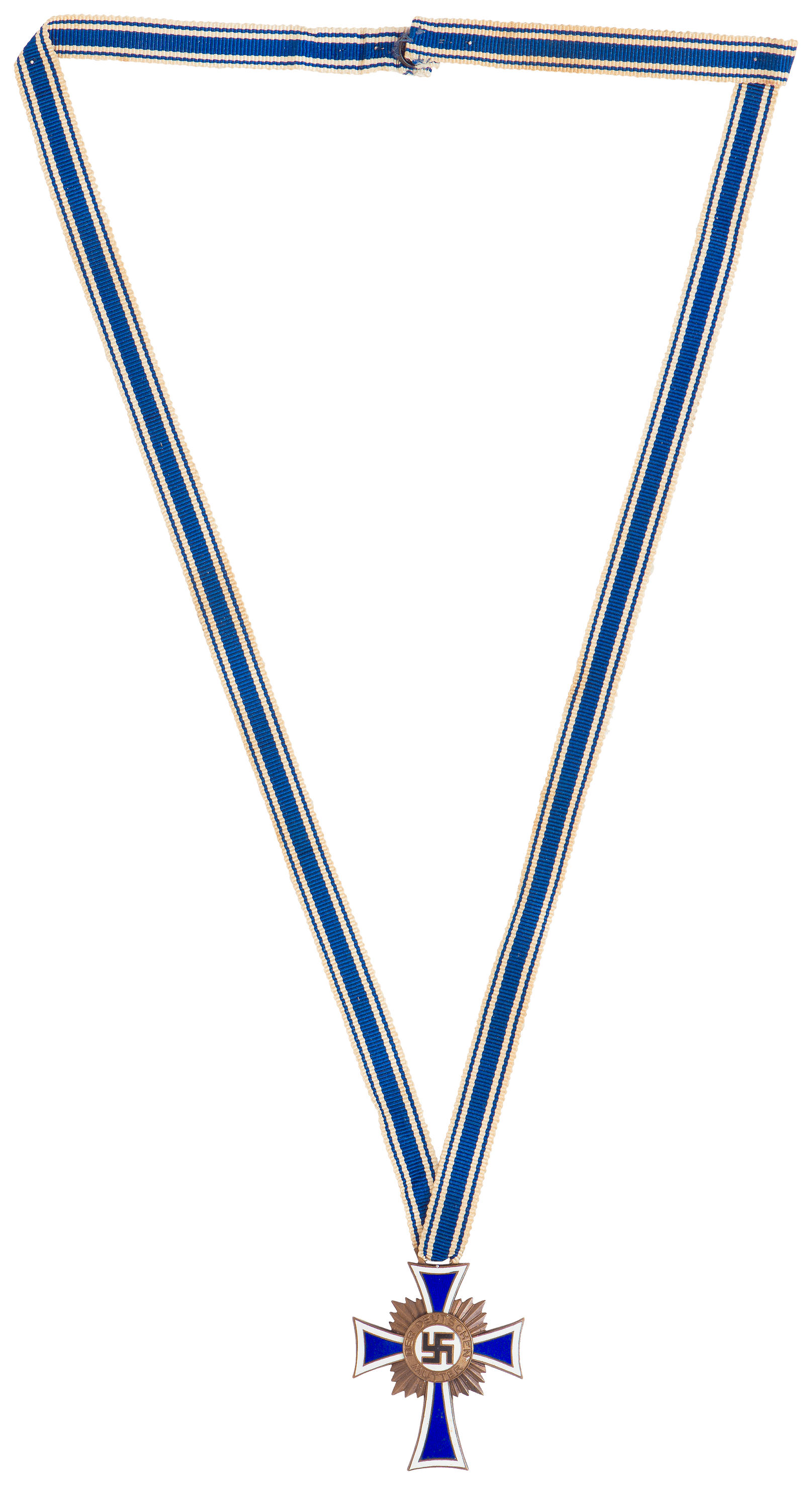

Gender Roles

The experiences of the First World War resulted in the breaking up of traditional relationships of roles. New public and professional fields of activity opened up for women. In 1918, they were granted the hard-won active and passive right to vote.

At the same time, there was an energetic counter-movement that sought to detect moral decay. Sexual orientations outside the heterosexual norm, extramarital relationships or homosexuality were rejected. In the post-war years and under the “Corporative State” dictatorship, some women were again forced out of jobs and public offices by law.

The ideology of National Socialism reduced men to militant masculinity. The role of women was redefined from a “racial” point of view: They were to secure the survival and “purity” of the “racial corpus”. Homosexual people were persecuted and murdered by the National Socialists.

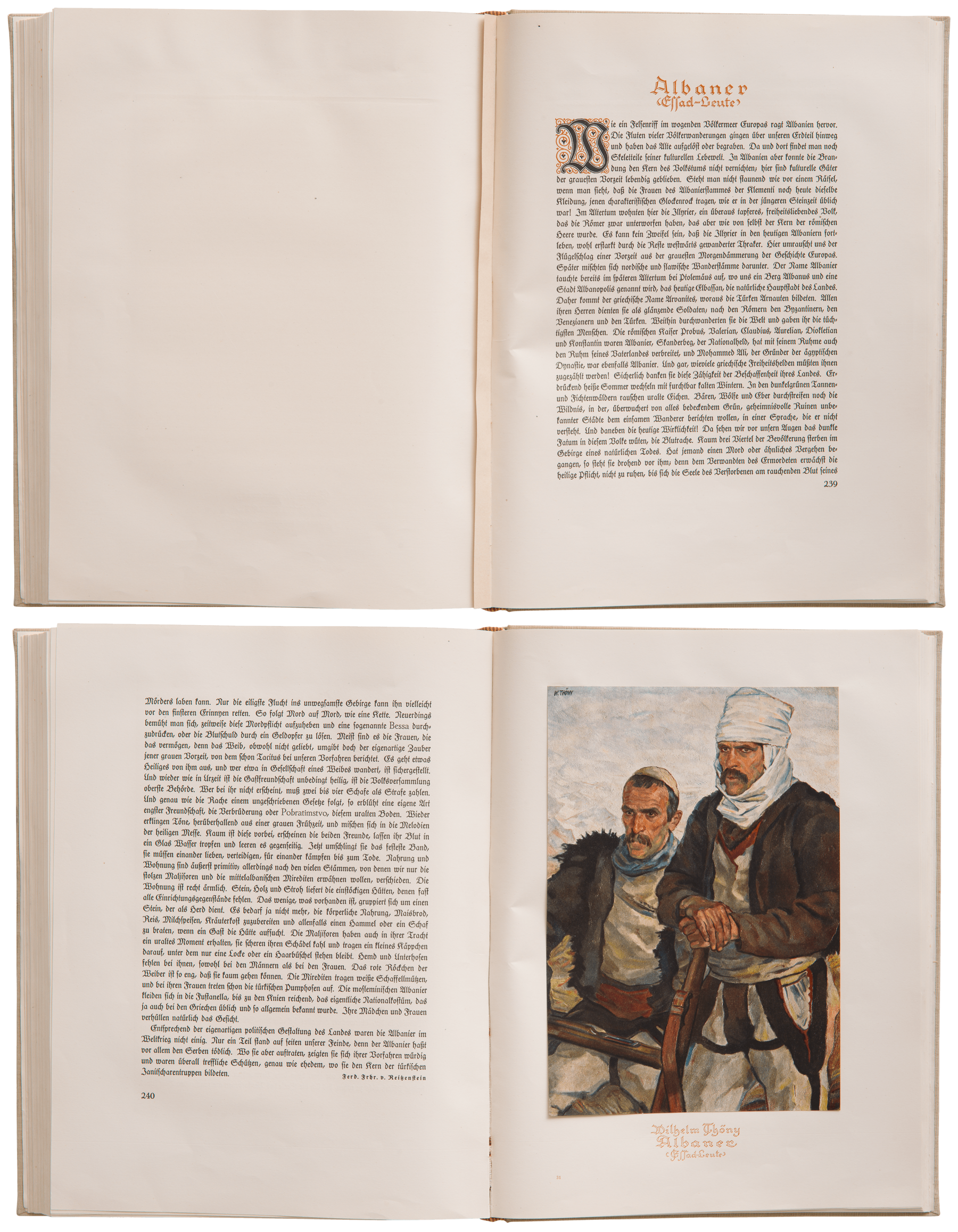

Diversity

The territorial reorganisation of Europe after the First World War also had far-reaching consequences for Styria. It lost one third of its territory to the SHS State (Kingdom of Yugoslavia). Only a few people had confidence in “residual Austria” and young democracy. In Styria, radically authoritarian tendencies and nationalist, anti-democratic, anti-socialist, anti-Semitic and anti-Slovenian sentiments were particularly pronounced. The NSDAP Austria was founded by a splinter group of the Styrian Home Guard.

The failure of democracy became apparent in the elimination of the Austrian parliament by Engelbert Dollfuß, the ban on party political opponents and the establishment of the “Corporative State” dictatorship. Despite a ban, many citizens of Graz, “the City of the Popular Uprising”, confessed to National Socialism in even before the “Anschluss” (the annexation of Austria). In March 1940, the mayor, SS Obersturmbannführer Julius Kaspar, declared the “Gau capital” “free of Jews”.

Images of the City

Around 1900, the city’s shape was essentially completed in the inner-city districts. The onerous housing shortage after the First World War had to be alleviated by the municipal administration with building residential complexes on the city’s periphery. Yet the city crucially changed through the incorporation of the surrounding communities, which had been discussed already before the turn of the twentieth century. Mayor Vinzenz Muchitsch pushed the project in the interwar period, but it was finalised in 1938 by the Nazi regime under the name of “Greater Graz” and within a few weeks.

The latter had further plans for the “City of the Popular Uprising”: massive road axes directed towards the Schloßberg, and solemn squares with monumental administration temples. In the end, the appearance of city Graz was spared this gigantic intervention. Yet it was not spared the air raids of the Allied Forces from late winter 1944 to Easter 1945. Almost 50% of all buildings of the city were damaged or destroyed.

Triestersiedlung

Unlike in Linz, nobody speaks of “Hitlerbauten” (Hitler Buildings) in Graz. One does not recognize that the foundation pillars of these buildings were completely delusional ideas addressed against (fi ctional) enemies, such as “keeping clean the Germanic blood” and the annihilation of the Judaism of the world. Hitler’s hatred against the “inferior” Slavs, who must be enslaved in the new territories of the East, is not expressed in these buildings. The banality of evil is practical and livable in the Südtirolersiedlung, which was once built for those “Germans” (i.e. the South Tyroleans) who opted against Mussolini.

Schießplatz Feliferhof

This hand grenade throwing range on the target practice grounds of the Feliferhof has inscribed itself in many people’s memory as a silent symbol of political crime. Far more than 300 people were executed here for “Wehrkraftzersetzung” (“subversion of the war effort” is one of the common translations), political resistance, and other reasons. In May 1945, a mass grave was opened where 142 bodies were found. Subsequently, they were buried with dignity at the central cemetery of Graz. In the frame of an annual mourning ceremony there, all victims of Nazi terror are commemorated.