Graz

1809–1914

The loss of the fortress in the early 19th century was only the beginning of rapid transformation processes. Industrialization and exploding population figures changed the cityscape. Newly established large factories attracted people to the city—the working class emerged.

The transformations also affected the social fabric. In various sections of the population, women strived for more self-determination and participation. The bourgeoisie found itself between enthusiasm for technical innovations and industrialization processes on the one hand, and nostalgia and fear of change on the other. Biedermeier idyll and modernization stood in contrast to each other.

The German National sentiments in the “most German city of the Monarchy” became more and more evident both culturally and politically.

The women’s bicycle from 1900 typically not only features a clothing net, but also a carbide lamp as a light source. This gas lamp was in use from the 1890s for buildings, bicycles and other vehicles. The fuel used was calcium carbide, which in combination with water released ethine gas for lighting. Some carbide lamps were popular until the 1950s because they were very lightweight, bright and relatively inexpensive. Then they were replaced by electric lighting.

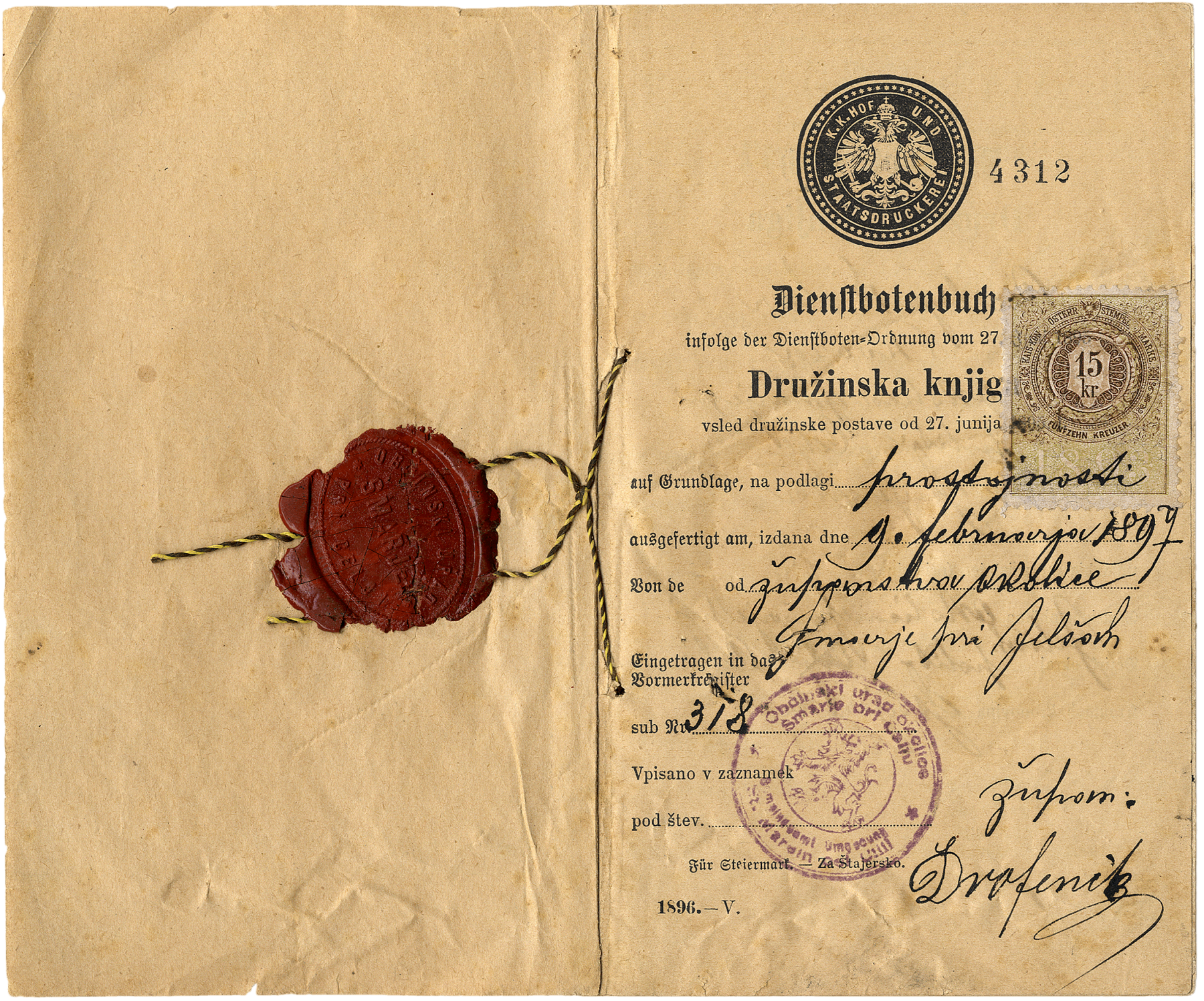

A “Windischer” (a Slovene) Brings Mobility to Austria

At the time when Janez Puh from Lower Styria (translator’s note: which is part of Slovenia today) moved up the ladder from small craftsman to factory owner, Graz transformed from a sleepy provincial city into an industrial and commercial centre. As it was linked to the south axis of the railway network by the route from Graz to Mürzzuschlag in 1844, the city was catapulted into the Industrial Age. Beside the Puch factories, other large companies such as the Reininghaus and Puntigam breweries, the Andritz machine works, the Weitzer railcar factory or the D. H. Pollak & Co shoe factory (today Humanic) tempted thousands of jobseekers from surrounding areas to come to the city.

The water from the Mur River was used for watering the fields, extinguishing fires, or—as can be seen here—for washing clothes. In the 19th century this was still heavy work, performed by women. The laundry was beaten with the hands, scrubbed, rinsed, wrung out, and hung over clotheslines in order to dry.

The chain bridge, which was named after Emperor Ferdinand I, was built by Franz Strohmeyer, the leaseholder of the “Überfuhr” (ferry) according to plans by the Vienna-based architect Johann Jäckl. It was the first chain bridge in Styria and the largest one in Austria. The Kepler Bridge stands at its place today.

The Rottal Mill with its two high gables, which belonged to the “Älteres Bäckerei-Consortium” (Older Bakery Consortium) is one of the enterprises that drew their energy from the left Mühlgang before the steam engine was introduced.

In the picture on the left there is a raft in the Mur River. In the early 19th century, the still unregulated river still serves as a transport route for people and goods.

The “Pruggmeier’sche Hadernstampfe” is a paper mill, i.e. a workshop where paper is produced of vegetable fibres and/or old rags. The paper produced this way was hung out to dry under the roof and in the garden.

Early Industrialization—a Graz Idyll

In the foreground, the tranquillity of the Biedermeier dominates the scenery. The Mühlgang hosted the main energy source of the time: the water wheels of the mills. But what actually takes centre stage is the new industrial age. In 1833, the first Styrian and at the time biggest Austrian chain bridge, the Ferdinand Chain Bridge, was built on the location of today’s Kepler Bridge. In order to hold the roadway, two massive brick-built chain houses on both banks of the Mur River were needed. What we owe to technical masterpieces like this one is also the expansion of railway lines.

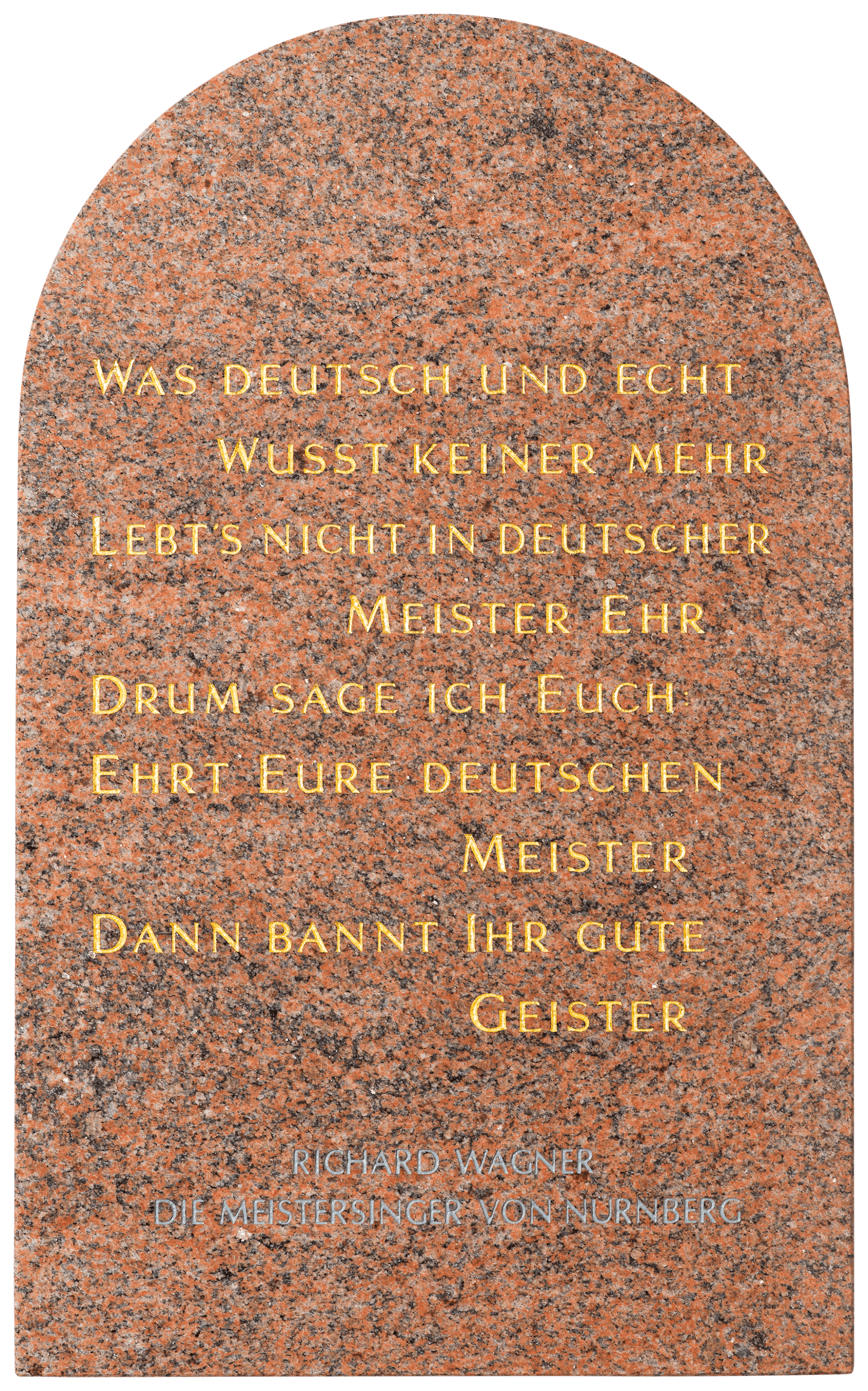

Graz, Nuremberg of the South

In 1897, when mayor Franz Graf took office, the decision for the construction of a new city theatre was taken. The city government’s cultural political driving force for this was clear: It was intended to become a German National sanctuary of the Wagner cult. In Graz, there was great enthusiasm for Richard Wagner, the leading figure of German-language cultural bourgeoisie. The marble plate on the backside of the present-day Graz Opera House bears witness to this with Hans Sachs’ verses from the opera “Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg“.

German Supremacy Starts to Falter

As a multi-ethnic empire, the Austro-Hungarian monarchy was characterised by a diversity of languages. The most common languages were German, Hungarian, Czech, Polish, Ukrainian, Romanian, Croatian, Serbian, Slovak, Slovenian and Italian. German was the dominant official language. From 1867, formal freedoms were granted to minorities in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Ten languages were permitted in the Imperial Assembly. Nevertheless, the demands for independence of individual nations became ever stronger.

Especially in Graz and Styria, as a border area to the Slavic region, German National tendencies increasingly emerged in the late 19th century. In 1889, the Verein Südmark was founded, an association with a large number of members, which advocated the use of the German language in border regions and German language islands in foreign-language regions. The influential association was marked by an increasingly hostile attitude towards the Slavs, which was shared by a large part of the population at that time.

Border of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy 1908 |

|

The Austro-Hungarian Monarchy is a multiethnic empire. The local administrations try to get an overview of ethnic affiliations by means of population censuses. Yet thereby it is not the nationality that is queried but the everyday language. The registered individuals often do not know which language to commit themselves to. Many Slovenes from Graz believe that they have to declare themselves as native speakers of German. Moreover, the uncounted minorities get lost in the identification of the relative majority. |

The Project of the City

In the 19th century too, the city was mainly responsible for social transformation and provided sanitary facilities, infrastructure, and cultural institutions. In the first half of the nineteenth century, Archduke John introduced the departure of the city of Graz into a technological and scientific knowledge society.

The Gründerzeit period of the 1870s and 1880s was marked by liberal bourgeoisie in Graz too. Individual freedom and freedom of property created the preconditions for a capitalist social order. The concept and way of life of the bourgeois were elevated to an ideal beyond social borders and the ruling social orders.

But the “bourgeois project” began to fragment and destroy itself in ideological power struggles. The uprooted petty bourgeois lower middle class sought new clarity in a manageable community with clear enemy images.

Gender Roles

The wife as housewife and mother, the husband as family breadwinner—that was the bourgeois ideal of the 19th century. At the same time, the calls to break down these rigid gender boundaries became ever more vehement. Women banded together in social, political, and economic movements. Noble and bourgeois women founded welfare and educational associations—like in Graz in 1848. Women workers organized themselves to claim fair wages, regular working hours, and increasingly women’s suffrage too.

The precondition for equality was the right to school education or vocational training—rights that had been hard-earned over time. In Graz, the first girls’ lyceum of the Monarchy opened in the building of today’s GrazMuseum in 1873. In 1898, the first woman was admitted to the University of Graz as a regular student.

Diversity

In Archduke John’s age, Enlightenment marked the mindsets of the educated people in the Masonic lodges, the academies, salons and reading circles. But the Austrian police state of State Chancellor Metternich created the opposite of a liberal society. Police informing, censorship and the restriction of freedom of expression were daily routine. Nevertheless: With the March Revolution of 1848 liberal tendencies emerged violently.

The system also addressed another phenomenon of that time: nationalism, which seemed incompatible with the many nations of the Hapsburg monarchy. After Metternich was overthrown, there were more and more forceful claims for national self-determination. Following Austria's defeat in the Austro-Prussian War in 1866, a “lesser German” nation state finally emerged. When the German Empire was proclaimed in 1870/71, many native speakers of German put their hopes in the new European great power—not only in Graz.

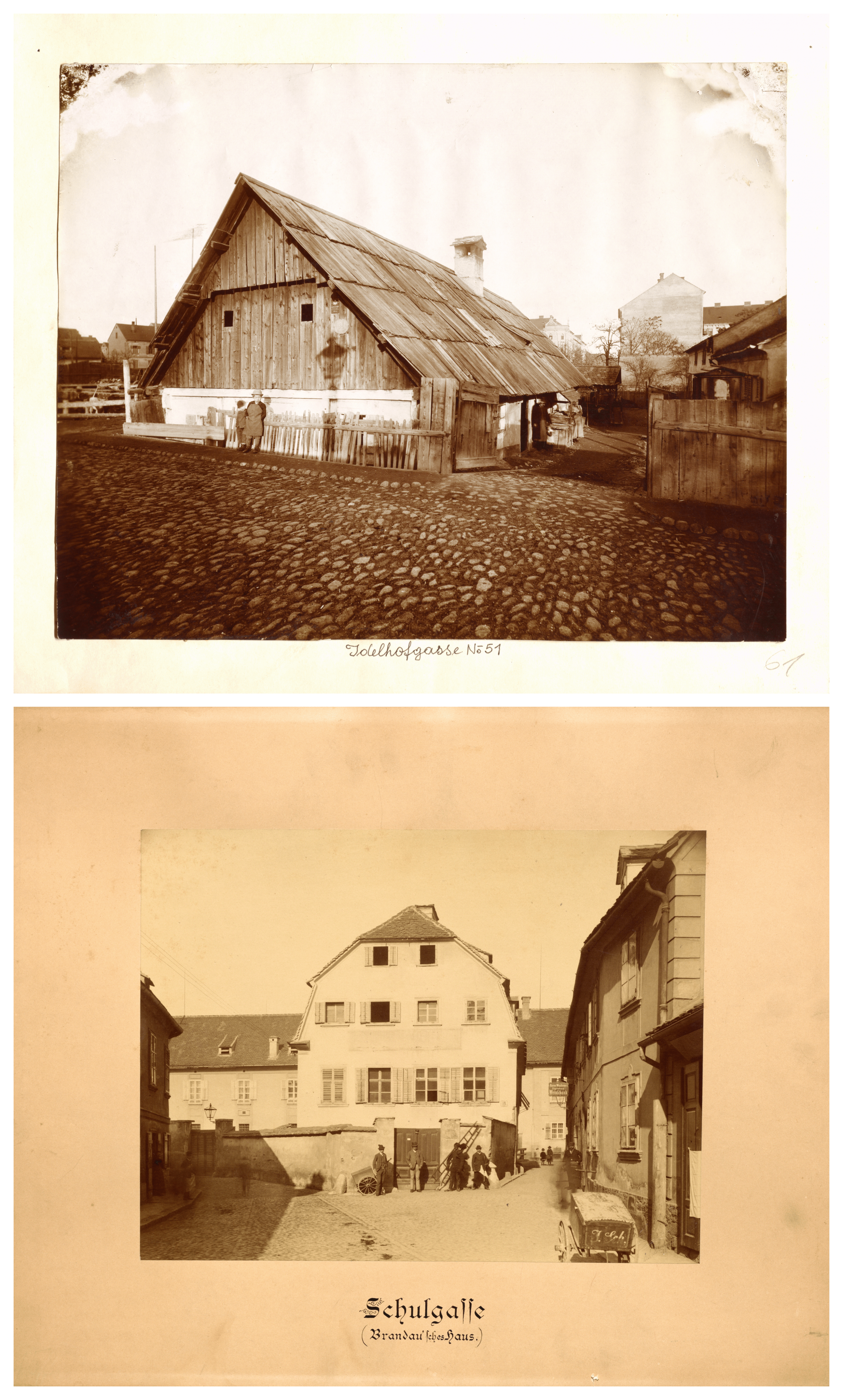

Images of the City

The fortress on the Schlossberg was blown up after the victory of the Napoleonic army over the Hapsburg troops in 1809 and the cityscape of Graz lost its most dominant landmark. Parts of the Grazer Burg and many of the fortifications, bastions and city gates were razed.

In its place, the ring road and the English gardens were built on the Schlossberg and in the Stadtpark. The Gründerzeit residential districts in Geidorf and St. Leonhard also developed. The noblest public square of Graz, the classicist Franzensplatz—today’s Freiheitsplatz—was built on the site of the former Hofgarten.

Traffic routes were regulated and realigned, modern large bridges connected the old town with the districts of Gries and Lend; at the same time, the Annenstraße towards Graz Main Station was built. Between 1885 and 1900 alone, 1,800 new buildings were erected. Thus, the core design of city of Graz as we know it today was completed.

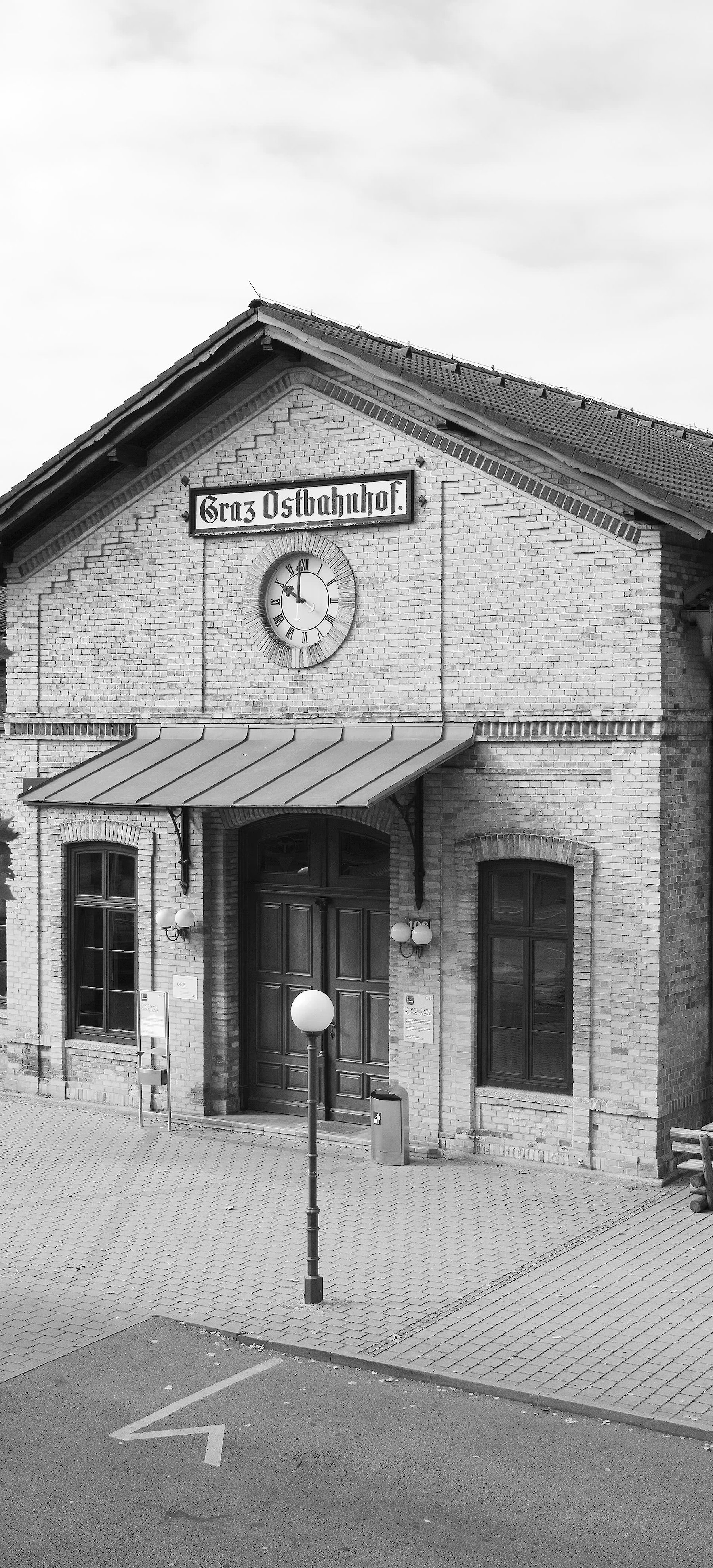

Ostbahnhof

In 1857, the railway line from Vienna to Trieste leading over the Semmering mountain was completed. That this line ran via Graz was rather due the imperial court’s fear of a revolution in Hungary (which was to be crushed in 1849) than Archduke John’s inflfl uence. For fear of this, the originally planned route via Hungary was discarded. Yet, when the Austro-Hungarian monarchy was established, the connection with Hungary was of course desired again. The Ostbahnhof (eastern railway station), the terminus of the Hungarian Westbahn (western line), which was built in 1873, bears witness to this.

Seifenfabrik

Due to the city’s underdeveloped transport infrastructure the industrial revolution initially went ahead very slowly in Graz. The university and administrative city was marked by small and medium-sized businesses for a long time. Nevertheless, industrialization, which set in around 1850, was the basis for the fact that the total population increased almost threefold until 1900. The Seifenfabrik (Soap Factory) in the workers’ district of Liebenau, which is used for all sorts of events today, is a monument of industrial history. But Graz could never at any time be characterized unequivocally as an industrial city.

Vinzenzkirche

In the second half of the 19th century, industrial Graz grew westward toward the railway. Thus the city was ultimately divided into two halves: in the west, on the other side of the Mur River, small craftsmen, lower middle-class and poor people and, farther to the west—around the factories—the workers’ accommodations. The wealthy educated classes, which built the Herz-Jesu-Kirche (Church of the Sacred Heart of Jesus) as their religious center, lived in the east. Inaugurated in 1895, the Vinzenzkirche in Eggenberg, a community which was outside the city limits at the time, was its western counterpart.

Landeskrankenhaus – Universitätsklinikum Graz

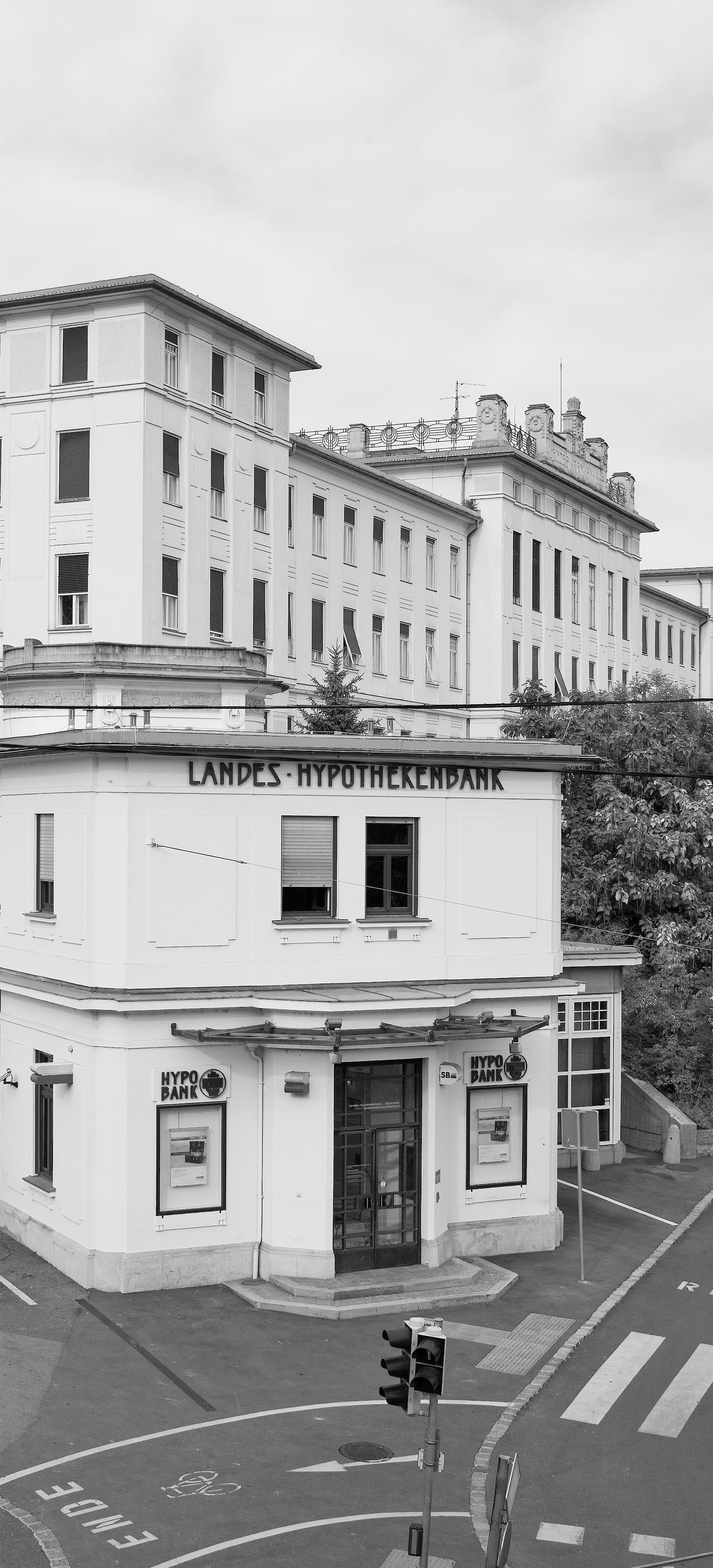

At the turn of the 20th century, the art nouveau buildings of Grand Hotel Wiesler, Hotel Erzherzog Johann, or the large department store Kastner & Öhler were among the few hallmarks of international modernity in Graz. The State Hospital, which also attracted plenty of attention on a supra-regional level, was another manifestation of this. Due to its location far outside the city center the project met fi erce opposition fi rst but its expansive arrangement of pavilions with subterranean connecting passages was soon accepted because of its superior functionality and Secessionist ornaments.

Städtisches Amtshaus

In 1885, Graz transformed from a bourgeois liberal to the “most German city of the monarchy”. Mayor Franz Graf was a hero acclaimed all over the “German countries”— for violent demonstrations which were staged as a struggle of races between the Teutons and the Slavs. In the case of representative buildings, such as the Städtische Amtshaus (municipal district offi ces building) of 1904, the nationalistic element directly or indirectly encouraged a building attitude which aimed at going through all styles in an (old) German manner. Liberals preferred Renaissance, German Nationals the Gothic style.

Herz-Jesu-Kirche

The private residential building—not the one located within the group of houses of a housing estate but the one immediately adjacent to the public street in a positive relationship—this urban pattern of the Gründerzeit is still most in demand according to the real estate price index. The peak of this is represented by the area around the Herz- Jesu-Kirche (Church of the Sacred Heart of Jesus), the neo-Gothic brick work building planned by Georg Hauberisser Jr., which dominates the architecture of the eastern part of the city. Today, its southwest tower, which was completed in 1887, is one of the highest ones in Austria.